The Difference Between Critical Literacy and Critical Race Theory (CRT):

The concept of critical literacy facilitates teachers’ ability to select and use children’s and young adult literature with their students in order to develop their educational lives as literacy learners. But before I discuss critical literacy, I think I need to explain what critical literacy is not. As education has become increasingly politicized, it’s very important for teachers to understand that critical literacy is not the same as critical race theory – often referred to as CRT.

Critical race theory is an intellectual field of study that originated with legal scholars and lawyers as a way to investigate structural disparities after the civil rights era. It is taught in universities and law schools – not in elementary, middle, or high schools. Those who launch protests and legal actions to remove critical race theory from public schools are ill-informed about the topic and tend to equate critical race theory with teaching the histories or about the people they think are not aligned with their own personal beliefs. For example, they sometimes seek to eliminate teaching about the civil rights movement because they think too much emphasis on critical points in our nation’s history when racism was even more pernicious than it is now is “woke” or leftist indoctrination that pits white people against minorities. And they advocate for banning books with LGBTQ characters or with characters of color or with other cultural backgrounds. I think it’s important for teachers to understand the difference between critical race theory and critical literacy. And, again, teachers need to understand that critical race theory is not something that is taught in K-12 schools. It is the domain of scholars in colleges, universities, and law schools. And, importantly, in my thirty-plus years in education, I’ve never heard a teacher tell white students that they should be ashamed of being white or discussed white people as oppressors or colonizers. Teachers are dedicated to valuing the diversity of their students and the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Critical Literacy is Derived from Critical Pedagogy:

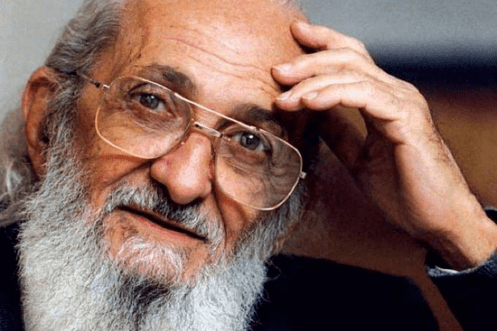

Critical literacy is derived from the critical pedagogy framework that was developed by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire who focused on adult literacy education in his home country. He was a critic of an education system that implemented what he called a banking model in which those in power decided what young students were taught. He advocated for a problem-posing curriculum in which students are participants in their education. In other words, education is not a passive process. Embedded within Freire’s philosophy of education is a devotion to freedom, justice, equity, and democracy.

The first tenet of his framework is praxis or practice that includes learning, action, and reflection. In the world of teachers, this means that we learn about theory, strategies, and methodologies; we then implement the strategies or methodologies with students; and then reflect on our practice and the impact on students. This is generally routine for teachers today.

The second tenet of Freire’s critical pedagogy is dialogue in which conversations and discussions are central to student learning. Again, learning is not a passive process of learning something in order to simply repeat it on an exam. We already know how important dialogue is in education as speaking and listening standards are commonly included in literacy and language arts standards because they are essential components of literacy development and learning all the various content areas in the educational lives of students.

Freire’s called the third tenant of critical pedagogy conscientization. In order to understand this concept, think about the word conscience. It is a process in which individuals become aware of their own lives and their place in the world – within their own families, communities, society, and the global planet we share with all humans. For teachers, this means a reflective journey in which students are invited to “read the word and the world.” And in the process, envision themselves as empowered to understand the world and in some capacity even create change and make improvements in order to create a better and more just society.

The Focus of Critical Literacy is Reading and Literacy:

Critical literacy extends critical pedagogy with a focus on reading and literacy. Its focus is on how we share and use literature and reading acts as empowering for students. It’s important to understand that critical literacy is not a method for teaching reading or a reading program implemented in a school. It doesn’t take the place of teaching foundational reading skills like phonics, story elements, comprehension or vocabulary.

The concept of critical literacy is sometimes taught in teacher preparation programs because it is important for teachers to be able to analyze the literature they share with their students and create literacy experiences that engage students’ immersive reading of texts as meaning-making actions. In reality, teachers often never use the term critical literacy when developing lessons for teaching their students – because it is not a method. However, teachers do generally have a criteria for selecting books they use to teach reading with their students and are thoughtful about how they use literature with their students to teach reading. I encourage teachers – those already working with students as well as those who are in teacher preparation programs to consider certain factors when selecting books to read aloud or ask students to read in class. For example, are the characters stereotyped? Are your students able to relate to the characters in the book? Do students of color in your class only see white students in the books you share with them? Is the information in the book accurate?

Teachers as Curators of the Literature They Share with Students:

Critical literacy practice means that teachers are careful curators of what they read to and with their students. Teachers shouldn’t simply pick up a book and read it to children without reading it themselves ahead of time. Reading aloud isn’t a time filler – something to do when you find you have five minutes to fill before lunch, for example. Nor should teachers read a book just to get to the end. Reading aloud is a fundamental component of reading instruction and is not a passive process.

Based on the critical literacy paradigm, teachers look to a criteria, either they’ve developed or have been developed by literacy researchers. Even highly popular and excellent children’s books authors write books that I choose not to share with children in my classroom. I don’t reject all their books, and I certainly don’t advocate “banning” them from my school library, I just choose not to use them in my classroom to teach reading.

For example, I love almost everything Eve Bunting has written. She has written many, many children’s books and has won several awards. However, as a teacher, I chose not to read two of her books with my elementary students because I do embrace the paradigm of critical literacy. One of them is A Day’s Work about a young Mexican boy living in California who joins his newly immigrated grandfather as he goes to work as a landscaper. The boy works alongside his abuelo and serves as his interpreter. The other Eve Bunting book I chose not to read with my students was Fly Away Home about a young boy who lives with his father at an airport after his father loses his job and home. My reasoning for not using these books was not an overt criticism of the author as much as it was, in my opinion, and others may disagree with me, that there was a subtle message embedded within the stories that good children, particularly children from poor or immigrant families, were good because they worked. They helped provide for their families. And this was not a message I wanted my students to learn. Another book I chose not to share with my class was A Chair for My Mother by Vera Williams because, this book, too, perpetuated the stereotype the good children from low-income families are good when they earn money for their family. In each of these three books, too, the children were working in a sort of “under-the-table” way, paid cash by employers. I think if a teacher decides to read these books with students, they should be older – perhaps upper elementary level or mid-level students who can be invited into a discussion about societal issues like child labor and the implications of the roles of adults who hire them. The discussion that ensues wouldn’t be mere criticisms but thinking deeply about the story. And, as Freire conceptualized Dialogue and Conscientization, consider alternatives for the characters in the story. In this sense, teachers invite students to read the word and the world; and then re-write the word to create a better world. What if the adults in the stories took an alternate path through small actions with regard to the children who are the main characters. In A Chair for my Mother, the woman who owns the diner where the child’s mother works pays the little girl to fill salt shakers and do other small tasks. But – what if the owner of the diner paid the mother a higher wage so the child didn’t feel that she needed to work. The child appeared to enjoy the work and was grateful, but what if the owner of the diner felt that it was more important for the child to spend her time playing outside, doing her homework, or reading good books?

Critical literacy suggests that teachers should enable students to understand perspective. For example, understanding the perspective of the various characters in the story. But also the perspective of the author. Sometimes we ask if the author has the background or life experiences to enable them to accurately or authentically write about the lives of the characters in a book. And sometimes we can lead students through an exercise in which a story is told from the perspective of a different character in the book. Authors Jon Sciezka and Lane Smith created an excellent example of the importance of perspective with their amusing rendition of The True Story of the Three Little Pigs in which the fairy tale is told from the perspective of the wolf.

The concept of critical literacy is particularly important when sharing multi-cultural books. For example, the Nambe’ Pueblo scholar and founder of the American Indians in Children’s Literature organization, Debbie Reese, provides a checklist for teachers to use in evaluating books that feature native and indigenous people, who have commonly been misrepresented and stereotyped in literature.*

Critical literacy is a framework or paradigm that empowers both teachers and students to think more deeply about the texts they read. Importantly, it creates deeper comprehension and engagement. And sometimes it can open up opportunities for students to engage in actions that improve their communities. For example, students may decide to write a letter from their class to a school administrator about something they care about – like providing school supplies for students who can’t afford them, or visiting a food bank to help with organizing the shelves, or inviting someone from the park services to talk about how to protect the resources the park provides. Remember that embedded within the paradigm of critical literacy is active participatory learning. And, importantly, it empowers students to be engaged in literacy as well as in life.

*The “Worksheet for Selecting Native American Children’s Literature” is available at https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/pdf/Native-American-Literature-in-Your-Classroom-Worksheet.pdf.

Leave a comment